Peace in Colombia isn’t in jeopardy. It’s already dead, and the peace accord with the FARC made things worse

With the election just three days away, many Colombia-watchers in the foreign press have been wondering out loud what might happen to the peace process if right-wing frontrunner Ivan Duque takes the presidency. He has promised not to scrap the whole endeavor, but rather make “structural changes” to the peace deal with the former FARC guerrillas. But we must take what Duque says with a large grain of salt; if he takes power, it will usher in a return to uribismo, of ‘Uribe 2.0’ as it were, and all the hatred and hardened militarism that comes with it. A Duque victory means that ex-president and sitting Senator Alvaro Uribe will be in charge of things – vicariously of course – but nonetheless the one pulling the strings connected to the dancing puppet-president. The proverbial Vladimir Putin to his Dmitry Medvedev.

For now, all of that is beside the point. The point is that with Colombia, the Western news media suffers from a kind of collective cognitive dissonance. In late 2016, they were all united in celebration: it was Colombia’s coming-out party. The country had finally woken up from its half-century-long stupor of violent conflict, we were told, and was now ready to be welcomed back into the international community. The future never looked brighter – there was peace in Colombia, and that its president was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts proved it.

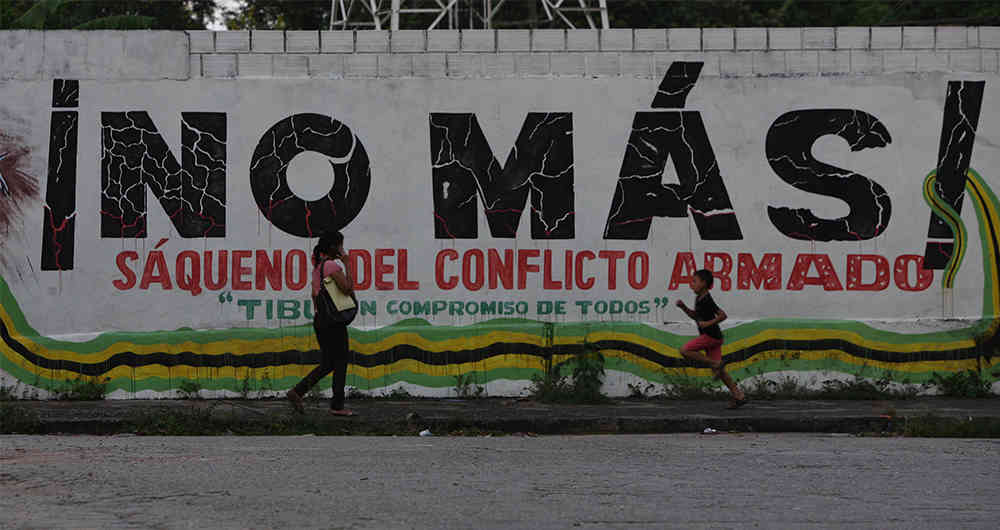

The torrent of kudos has since died down, and we continue to read about Colombia, but it doesn’t sound like a country at peace. That’s because it isn’t. For all the fanfare around “post-conflict” Colombia, the peace deal with the FARC has actually led to an increase in the very kind of violence that it was supposed to end. It’s easy to dismiss this as hyperbole if you live in one of Colombia’s cities, but outside these little bubbles of relative stability plays a very familiar refrain: turf war, drug trafficking, murder, kidnapping, and terrified innocents fleeing their homes.

Peace in Colombia exists only on the piece of paper President Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC leadership signed in 2016, and even that is in tatters. If you need more convincing, here are five reasons why there is little reason to be optimistic about Colombia’s “farewell to arms”:

1. Colombia Has Failed to Deliver on its Peace Commitments

The man who was the toast of the world for successfully negotiating a peace agreement with Colombia’s largest guerrilla group has done a dismal job in following through with its implementation. With Nobel Peace Prize in hand, President Santos simply delegated all the hard work of peace-building to a largely indifferent Congress and hastily-formed bureaucratic apparatus like the High Commission for Peace.

Not even 20 percent of the responsibilities outlined in the 17-month-old agreement have been met, and a good portion of what has been done was held up in Congress for nearly a year. Essential parts of the peace accord, like rural reform – upon which other aspects of the agreement rest – have barely been discussed, let alone implemented. And like everything else in Colombia, that which has moved forward has been marred by allegations of corruption and a lack of transparency.

Donor countries have grown impatient with the disorganized patchwork with which the accord has been rolled out, and have demanded that the government explain what’s going on. This diplomatic rap-on-the-knuckles came as a blow to credibility of the peace process and President Santos should be embarrassed.

Demobilized FARC fighters listen to a commander speak just before surrendering their weapons in a reintegration camp, on February 28, 2017.

For its part, the United Nations’ High Commission for Human Rights said it was “deeply concerned” with the continued impunity for the murder of social leaders and human rights defenders, as well as Congress for preventing the appointment of some judges to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace war crimes tribunal (which goes by the Spanish acronym JEP). Much of the administration of the peace agreement “does not comply with international standards,” the UN High Commission stated, and warned that the International Criminal Court (ICC) may have to intervene if Colombia can’t get its shit together.

The manner in which the accord is supposed to help the average guerrilla reintegrate into society has also been an utter failure. Thousands of rank-and-file fighters have languished for months in one of the 26 reintegration camps scattered around the country, and many have grown fed up with waiting around and have left. Some simply went home to their families. In other cases, clusters of rebel fighters have decided to return to their old guerrilla camps in the jungle. Still others have been lured away with the promise of money and purpose by one or another of the mishmash of illegal armed groups that have filled the vacuum left by the FARC. By some estimates, up to 55 percent have deserted the reintegration camps, meaning that there are roughly 4,000 ex-guerrillas unaccounted for.

And of those, some 1,200 guerrillas are thought to have rearmed and taken up defensive positions in the field. Some heavy hitters within the FARC have joined them, including Ivan Marquez – one of the organization’s top leaders and a key negotiator in the peace talks in Havana. Fearing he might be captured next, Marquez fled to one of the reintegration zones in the southern province of Caqueta after the arrest of Seuxis Hernandez, aka Jesus Santrich, another high-ranking member of the FARC’s political leadership.

Marquez and another FARC head who goes by the nom de guerre ‘El Paisa’ – a field commander of the feared Teofil Forero guerrilla column – has also left the demobilization camp, along with an unknown number of followers, and their whereabouts are currently unknown. A growing number of demobilized FARC fighters have lost faith in the peace process, and many would rather continue their insurrection than to be murdered while in the camps, and the arrest of one of their top commanders and another going into hiding (and possibly rearming) is enough for them to read the writing on the wall. It will be a miracle if this alone doesn’t kill the peace process, let alone a state of peace in Colombia.

2. Arrest of FARC Leader May Sink the Peace Deal

The FARC-Colombia peace accord edged further towards oblivion on April 9, with the arrest of Jesus Santrich, a high-ranking member of the FARC’s political leadership. Santrich is slated to be extradited to United States to face trial on charges of conspiring to traffic 10 metric-tons of cocaine to Mexico’s infamous Sinaloa drug cartel in November 2017 (though his lawyers and some leftist politicians are fighting the extradition). The blind guerilla, who was instrumental in the peace negotiations in Havana, Cuba, was sent to the Picota prison in Bogota upon his arrest. He vehemently denies the charges and went on a hunger strike to protest his detainment. The 51-year-old had only been taking water and lost a substantial amount of weight. After 29 days behind bars, his health deteriorated to the point where he was transferred to El Tunal hospital on Monday, May 7, where he received medical treatment for malnourishment and hypoglycemia.

Since then, he has received a number of important visitors, including the European Union’s Special Envoy for Peace Eamon Gilmore; Head of the UN Mission in Colombia Jean Arnault; Norwegian Special Envoy to the Colombian peace process, Anne Heidi Kvalsoren; Cuban Ambassador to Colombia José Luis Ponce; and Father Francisco De Roux, a Jesuit priest and president of the peace process’ Truth Commission – all of whom implored Santrich to cease the hunger strike, and demanded he be allowed to submit testimony to the commission. The indicted guerrilla later agreed to do so, on the condition that instead of returning to his prison cell, he be transferred to a house belonging to the Catholic Church in Bogota, and he has been there, under guard, since May 10.

At least two Congressional seats reserved for the FARC leadership are likely to be vacant – that of Ivan Marquez, who went into hiding – and the one reserved for Jesus Santrich (pictured).

The evidence against Santrich, at least that which has been made public by the Attorney General’s Office, is inconclusive at best. Prosecutors have Santrich’s assistant, a man named Marlon Marin, speaking on the phone with someone the attorney general says is a member of the Mexican Sinaloa cartel. The conversation is largely in code, with the two men speaking about “avocados” and “delivering 5,000 TVs to Barranquilla.”

In the wiretapped conversations, Marin (who is a cousin of Ivan Marquez) does all the talking, and he and the alleged cartel member at one point refer to el ciego (the blind man), a reference to Santrich. But at no point in the evidence is Santrich heard speaking directly to the Mexican narco. He is only heard speaking to Marin, in a later-recorded conversation, about setting up an unspecified meeting.

It’s hardly a smoking gun against the former guerrilla commander, though it remains to be seen what kind of evidence the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has on el ciego. In any case, it’s safe to say that if President Santos makes good on his promise to extradite Santrich to the US, the peace process is as good as dead.

3. Dissident FARC Faction Kidnapping and Killing

There could not be more blunt a demonstration that peace is a mirage than the kidnapping and brutal murder of two journalists and their driver by a FARC dissident group in a region of southern Colombia that borders Ecuador. A man by the name of Walter Arizala, alias el “Guacho,” leads a merry band of murderers who call themselves the Oliver Sinisterra Front, a break-away faction of the FARC rebels who do not recognize the peace deal. They have become a public enemy No. 1 in both Ecuador and Colombia after chaining up their hostages like dogs for 18 days, and later shooting them all multiple times in the head and torso.

Aside from drug trafficking, the addition of kidnapping into the dissident faction’s cadre of criminal activities is new. They nabbed the three men: reporter Javier Ortega, photographer Paul Rivas – both journalists for El Comercio newspaper – and their driver, Efraín Segarra, on March 26 in the crime- and poverty-stricken border region not far from the southern Colombian port town of Tumaco. They were last seen alive on April 3, when a video emerged showing them chained together by their necks, begging the Ecuadoran government to comply with their captor’s demands. They said the group was demanding a prisoner exchange and an end to the Colombia-Ecuador joint military operations in the area.

A screengrab from the video released by the FARC splinter group, showing, from left: photographer Paul Rivas, reporter Javier Ortega, and their driver, Efraín Segarra.

When a letter surfaced on April 11, claiming to be a communique from the dissident rebels that the hostages had been executed, Ecuadoran President Lenin Moreno gave the group 12 hours to provide proof of life, but it never came, and on Friday, April 13, Moreno confirmed that the hostages had been assassinated.

Since then, as hundreds of Ecuadorans mourned their murdered countrymen, both Colombia and Ecuador have stepped up military operations in the border region, and on April 30, el Guacho proposed a ceasefire so that the bodies of the people they murdered could be repatriated to Ecuador. President Moreno has balked at the idea, and the bodies have to this day not been returned to their families for a proper burial.

The bodies of Segarra, Ortega and Rivas after being murdered by FARC dissidents.

Five days after the three men were killed, the dissidents kidnapped an Ecuadoran couple on the Colombian side of the border, and they were accused by the rebel group of being spies. They too appeared in a video pleading with President Moreno to negotiate with the group “so that they do not meet the same fate as the journalists.” But since that video there has been silence – no further proof of life, no communique claiming the couple had been killed – nothing.

Related: 5 Reasons Not to Negotiate With the ELN

There are dissident FARC rebel factions elsewhere as well. Aside from the 80 fighters under el Guacho’s command, two other dissident guerrilla groups – the Gente del Orden and the Guerrillas Unidas del Pacifico – are present in the same region. Analysts believe that the three groups have more than 500 active members. Add that to the thousands of FARC guerrillas who have fled the reintegration camps, and it doesn’t look like the process of reintroducing fighters into civilian life is going well.

4. ELN-EPL Turf War, Gang Battles in Medellin, ‘BACRIM’ in Ciudad Bolivar

While dissident FARC splinter groups are active in Nariño, Cauca, Valle de Cauca and Chocó provinces, violent clashes continue to be the norm between other armed groups in central and northeast Colombia as well.

In the Catatumbo region of Norte de Santander, a northeastern province that borders Venezuela, the ELN and a smaller guerrilla group known as the Popular Liberation Army (EPL) have turned the region into a battleground as they fight for control of a treasure-trove of illicit holdings in the area, including the lucrative drug trafficking and crude oil smuggling routes, as well as 20,000 hectares of coca fields. In the month of April alone, clashes between rival guerrilla factions have forced more than 6,000 people in Catatumbo to flee their homes. The government says eight people have died in the fighting, but human rights groups put the number of dead at 30.

In an attempt to quell the violence, the Colombian government said it would send three new battalions of made up of 6,000 soldiers and 2,000 police to Catatumbo – on top of the 10,000 troops already stationed in the region. But residents there who have stayed and coped with the turf-war say that government troops have done little to improve the security situation.

A column of ELN guerrillas seen on the march in this undated file photo.

An equally bad flare-up in violence took place in Medellin, Colombia’s second city, late last month. The military had taken over parts of the city after a broad-daylight shootout between members of the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) neo-paramilitary group and the ‘Oficina de Envigado’ drug gang, in Medellin’s Comuna 13. Despite a national downward trend, homicides in Medellin have spiked in 2018, with 197 murders seen in the city so far this year.

Things are no better in the Colombian capital. There is an increasing presence of at least five, possibly six different ‘BACRIM’ groups in the impoverished Ciudad Bolivar district in Bogota’s south. These groups include the AGC, the ‘Rastrojos’ drug trafficking syndicate, the far-right Aguilas Negras (Black Eagles) paramilitary group, the ‘Paisas’ drug gang, the ELN, and maybe even a group of FARC dissidents. This according to a report released to the media by Colombia’s Ombudsman Carlos Negret.

“The presence of these groups have led to forced displacements, threats, extortion, and even the requirement of residents and businesses to pay ‘protection’ to one group or another,” Negret was quoted by El Tiempo as saying. He also warned that vulnerable youth in the area are susceptible to being recruited by the groups, and that locals have been threatened with so-called “social cleansing” campaigns aimed at killing “ratas”: drug addicts, homeless people and petty criminals.

The murder rate is also up in Bogota’s south. Between January and February of this year, there were 45 homicides in Ciudad Bolivar, 14 more than were seen during the same period of 2017.

5. Human Rights Defenders are Butchered by the Dozen

There’s a line in the Netflix series ‘Narcos’ that the only thing more dangerous than being a cop in Colombia was a presidential candidate who backed the extradition of criminals to the United States. This might have been true in the 1980s, during Pablo Escobar’s reign of terror, but in today’s Colombia, there is an even more perilous occupation – people who stand up for human rights.

The wholesale slaughter of human rights defenders and community leaders – murders which almost always go unsolved and which the killers commit with impunity – has skyrocketed after the Colombia-FARC peace accord. A staggering 121 social leaders were murdered in Colombia in 2017, nearly double the number of those killed the previous year, according to figures released by the United Nations.

And with 46 assassinated so far this year, 2018 is well on course to beat the 2017 record of community organizers, land reform advocates and human rights defenders who die for daring to speak up for the poor, the terrorized, the displaced and the landless. It can even be said that the peace accord contributed to the spike in killings. One cause of the rise in murders is that right-wing paramilitary gangs and other armed groups have entered into territory previously held by the FARC. Community leaders who challenge their presence become what is colloquially referred to as “military objectives.” Those who defend the rights of displaced people to return to their land are especially targeted, research shows.

Demonstrators hold up signs commemorating human rights defenders and community leaders who have been murdered in Colombia, in this undated file photo.

Earlier this month, Luis Guillermo Perez Casas, a lawyer with the Colombian rights group Colectivo de Abogados José Alvear Restrepo (CCAJAR), submitted a report to the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights. In it, he said the systematic nature of the killings, the scale, and the failure of the Colombian government to investigate them has reached the threshold of crimes against humanity.

“The murders of our colleagues must stop,” Perez was quoted by The Guardian as saying. “We hope the Office of the Prosecutor of the (International Criminal Court) will warn the Colombian government that if the impunity persists, they will be forced to open an investigation into those responsible, at the highest level.”

Colombia has been under the microscope of the ICC since 2004, and if they conclude that there is widespread and systematic attacks directed at the civilian population by state or state-like actors (there is certainly plenty of evidence for it!), then the court could intervene and begin prosecutions against criminal actors, experts say.

***

The government has demonstrated that it can’t (or won’t) stop the killing, so if there’s any hope of salvaging any tiny portion of the quiet that still remains, then foreign intervention is needed. Colombia has its war crime tribunal up and running, but if the peace process collapses, the tribunal goes down with it. And even if it endures, there is nothing within its power that is likely to curtail the scores who are murdered under the oppressive control of one armed group of thugs or another.

Most victims flee after watching family members or neighbors killed, while others are driven from their homes, and become refugees in their own country. Since the signing of the peace agreement in November 2016, more than 150,000 people have been displaced – the equivalent of one person every four minutes. The rural displaced become the city-dwelling homeless, they do whatever it takes to survive, and a new cycle of violence begins all over again.

Ending the conflict with the FARC didn’t bring peace to Colombia like it was supposed to. It made things worse. The time has come for foreign intervention, in the form of the ICC, no doubt. But bold thinking is also needed – like deploying a large contingent of UN Peacekeepers to various hot-spots around the country.

An end to violence remains allusive, so it needs to come from the outside world. Without it, maybe peace in Colombia was too much to hope for. Why would anyone expect that a people who have been deprived of both peace and justice for the past half century would be able to administer such things themselves?

Journalist. Misfit. Malcontent. Provocateur. Is a better Colombia is possible? We’re starting to have doubts.

Pingback:It’s Time to Defund Colombia’s Military | MiKolombia.com

Pingback:The FARC Guerrillas as Hezbollah, Venezuela as Iran | MiKolombia.com

Pingback:‘When the News is Very Sad I Cry’ | MiKolombia.com

Pingback:Colombia 'Choosing Between AIDS and Cancer'? | MiKolombia.com

I liked the article. excellent research,